Mirror Mirror in this winged baby’s hand,

Who’s the fairest in the land?

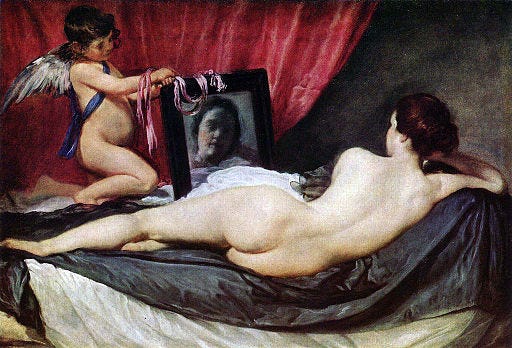

What: The Toilet of Venus or The Rokeby Venus (1644ish) by Diego Velázquez

Where: The National Gallery in London, England

I would like to talk about three different works of art that simultaneously have nothing in common and are all related. Let’s cover them in reverse chronological order.

Part 1: An Enemy of the People

On March 14, 2024, the Broadway revival of Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People starring Succession’s Jeremy Strong played one of its last previews before its official opening, mostly to an audience filled with members of the press. There are a lot of nouns in that sentence, so perhaps I should give a little bit of background on a few of them. Jeremy Strong is an actor who studied at both Yale and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. His love of using the word “dramaturgically” and his devotion to an acting practice known as “identity diffusion” have been exasperating colleagues ever since. If you are ever planning on talking to Jeremy Strong, you need to know that “identity diffusion” is absolutely not the same thing as “method acting”. If you are never planning on talking to Jeremy Strong, “identity diffusion” is a new-fangled way of saying “method acting.”

Henrik Ibsen was a remarkably successful dramatist. Famous literary criticism website visitnorway.com characterizes Ibsen thusly (the bolding and exclamation points are theirs):

Ibsen is undoubtedly one of the greatest playwrights in the universe. So naturally, The International Astronomical Union named a planet after him. Only a minor planet, but still! …if you really want to experience Ibsen’s plays like you were meant to, you need to do like James Joyce did - learn Norwegian!

Perhaps Ibsen’s most famous work is the Norwegian romantic mythological drama Peer Gynt, which was partially inspired by the life of a real Norwegian violinist who accidentally led a bunch of other Norwegians to their death attempting to build a castle in the woods of rural northern Pennsylvania. That play is better known as the source of Edvard Grieg’s music Peer Gynt Suite, which of course inspired the 1970 flop musical film Song of Norway, starring Carol Brady herself, Florence Henderson, as Nina Grieg.

An Enemy of the People is one of Ibsen’s other works. In it, a socially awkward doctor (J. Strong) lives and works in a small spa town where his brother is the mayor. The doctor discovers an environmental health crisis, and attempts to get the town to agree to temporarily close the contaminated spas. The doctor realizes that shutting down the spas will bring about some economic problems for the town, but takes solace knowing that his work uncovering the contamination will prevent significant harm. At first, many members of the town support the doctor, although his mayor brother does not. His attempts to convince the town to close the contaminated spas eventually lead to his ostracism as members of the community one by one find ways to excuse their pursuit of profits over public safety. At one point, the townspeople turn on the doctor so completely that they attack his home, breaking the windows and wrecking the study. The play combines two themes near and dear to my heart: environmental regulation and people who are right about everything, but are also kind of annoying. The person who cast Jeremy Strong as the doctor clearly deserves a MacArthur Genius Grant.

The revival of An Enemy of the People was performed as a semi-immersive piece; the scenic designers built out a semi-functioning bar that served aquavit to audience members in the middle of Circle in the Square’s thrust stage. This atmosphere only added to the confusion on that March evening when the shouting started. The play had just progressed to the dramatic climax, a tense scene set at a meeting where the town members would turn against Strong’s doctor. However, the shouters were not paid actors, they were audience members, and their environmental concerns were not about the waters of one Norwegian spa, they were about global climate change. Three representatives of the group Extinction Rebellion had decided to interrupt the play with speeches of their own about environmental regulation and community responsibility. Not helping the potential confusion, not-method actor Jeremy Strong started responding to these environmental activists seemingly in character.

At this point you may be thinking, wait what does this have to do with general butts let alone the specific butt of the Rokeby Venus? Was this a particularly bum-centric production? Is Jeremy Strong known for his voluptuous derriere? No and no, but you know that had Ibsen inspired Grieg to write Experience Unlimited’s “Da Butt” instead of “Anitra’s Dance”, then Strong would have performed the entire first act while doing split squats and the entire second act while twerking. Alas. No, in fact this entire anecdote has virtually nothing to do with butts, but it does relate to a piece of art, not by Velázquez, but by Degas. Two of the protestors kept their message mainly about the environment. They are quoted as having said, "I object to the silencing of scientists!”; "The oceans are acidifying! The oceans are rising and will swallow this city and this entire theater whole!"; and "The water is coming for us! Broadway will not survive on a dead planet!" The third protestor, however, also shouted the names Tim Martin and Joanna Smith.

Part 2: Little Dancer, Age Fourteen.

Almost a year earlier, on April 27, 2023, Tim Martin and Joanna Smith entered the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. They did not, as far as I am aware, go see Bachiacca’s The Flagellation of Christ. Instead, they went to the first-floor sculpture gallery, took out two bottles they had surreptitiously filled with paint, and began to smear the vitrine surrounding Edgar Degas’s Little Dancer, Age Fourteen with that paint.

Degas’s Little Dancer, Age 14 outside its protective case.

First, a little bit about both the statue and the vitrine, as this may be important later. While fellow artists knew that Degas was a sculptor of some competence (Renoir thought he was the greatest sculptor since antiquity, better than Rodin), he was not known as a sculptor to the general public. In fact, while Degas made hundreds of small-scale statues as studies for his paintings and several larger works for his own enjoyment, Little Dancer, Age 14 was the only sculpture he would publicly exhibit during his lifetime. Made of beeswax, clay, metal, wood, human hair, and rope, the sculpture is a one-third life sized representation of the young Paris Opera dancer Marie van Goethem. Degas installed a glass vitrine for the work at the 1880 exhibition with his fellow “Impressionists,” but the statue was never displayed. He again installed the glass cage at the 1881 exhibition, and the figure appeared two weeks later. This is the work that is now on view, and highly publicized for that matter, at the National Gallery of Art.

Well, that’s not exactly true. Degas’s original vitrine is now lost; so the vitrine at the National Gallery is simply a functional box that protects the wax statue from the elements. Also, the work that exists in D.C. is not the original statue so much as it is a reworking of that statue that Degas tinkered with between 1903 and his death. A plaster cast of the original, long thought to be a fake but now mostly considered genuine, shows the original statue had several prominent differences, including a different posture and positioning. It is also possible the skirt on the statue is also not original; the National Gallery itself calls the situation “murky.” Evidence suggests the tutu was replaced twice, but it is possible the current skirt includes material from the original. Either way, art historians and specialists cannot even agree what exactly the tutu might have looked like when the statue premiered. Thus, the Degas in Washington is not exactly the Degas that was on display in 1881. Also note that several bronze castings of both the reworked wax statue and the plaster capture of the original are now also on display in museums across the world.

Tim Martin and Joanna Smith, activists with the organization “Declare Emergency” said the purpose of their protest was to demand President Joe Biden declare a climate emergency and stop issuing new drilling permits and subsidies for fossil fuels. While their protest did not damage the Degas statue, different news outlets quote authorities saying the incident cost between $2,400 and $4,000 in museum repairs. Within a month of their actions, Martin and Smith had been indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States and injury to an exhibit or property at the museum. They faced up to five years in prison and a fine up to $250,000.

Climate and environmental activists had staged other protests involving museum displays; one estimate suggests there were over 80 “significant protest actions” at art museums +/- one year from the event at the National Gallery. However, it was the specificity of the charges and their potential for extended prison sentences that connected the Little Dancer, Age 14 event and the An Enemy of the People protest. The theater disruptors had wanted to provoke the public to consider how someone could be charged with “conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States” if they had specifically chosen a method of protest that had no likelihood of damaging any artwork. One month after the An Enemy of the People protest, Smith was sentenced to 60 days in prison. As of the time I’m writing this, Martin’s case had not yet gone to trial.

Part 3: The Rokeby Venus

One month and 109 years before Martin and Smith threw paint on a glass box in a museum, on March 10, 1914, journalist and art student Mary Richardson walked into a different National Gallery, the one in London. Unlike Martin and Smith, she did go to see a painting that featured a very prominent rear end, namely Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus (Rokeby Venus), Velázquez’s only surviving female nude. That day, Mary Richardson did not have a water bottle filled with paint on her person. However, she did have a sketchbook and, more relevant to her ultimate purpose, a meat cleaver. With the cleaver she would go on to slash and chop several large holes into the Rokeby Venus in protest for women’s suffrage. She had every intention of damaging the artwork.

Seventeenth-century Spanish art was monitored and censored by the Spanish Inquisition, making female nudes from that time and place quite rare. Artists had painted reclining Venuses before Velázquez including Titian and Giorgione, but these forerunners did not show Venus’s sizeable backside. The painting had belonged to the art dealer Domingo Guerra Coronel and was sold to Gaspar Méndez de Haro, a Spanish noble and well-known libertine. The painting, and in fact most of Velázquez’s works, were not considered important to the Western art history canon until the 19th century. Even in Spain, Velázquez’s works went through periods of relative obscurity. The work was likely looted from the Spanish, and fell into British hands in 1813. John Merritt eventually purchased the painting and hung it in his house at Rokeby Park, which is how it got the name the Rokeby Venus.

Richardson’s actions were specifically protesting the arrest of fellow suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst. Richardson wrote at the time:

“I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as color and outline on canvas.”

The Rokeby Venus as damaged by Mary Richardson

Emmeline Pankhurst was the principal organizer of what may be considered the most militant wing of the suffrage movement in Great Britain and Ireland. She founded the Women's Franchise League, an early co-ed activist organization that advocated for women’s suffrage, and later the Women’s Social and Political Union, an all-women organization (WSPU). The WSPU almost immediately adopted physically confrontational tactics. The members smashed windows, physically engaged with law enforcement, interrupted public gatherings, and set over 100 buildings on fire. Pankhurst did not shy away from prison, she sometimes took deliberate action to goad police into arresting her.

While in prison, she staged hunger strikes that were met with violent force feeding. When the aristocrat Constance Lytton joined the suffragists in Holloway Prison, she chose as the canvas for her protest not a Velázquez nude, but her own body; she decided to inscribe the phrase “Votes for Women” across her chest using nothing but a hairpin. She got as far as the “V” before she was stopped and bandaged by medical staff. (Her grandfather, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, is the originator of the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night…” from his novel Paul Clifford. He wrote on paper.)

Perhaps the most famous suffragist incident as precursor to Mary Richardson was Emily Davison. Emily Davison was an incredibly active suffragist. She had joined several of the hunger strikes in Holloway Prison; she claimed to have been violently force fed nearly 50 times. In 1913 she attended the Epsom Derby. Mary Richardson was perhaps in the stands (she later said she was in attendance). Mid-race, Emily Davison ducked under the railing and charged onto the racecourse. She was hit by King George V’s horse Anmer and died four days later. The entire incident was captured by news cameras. While it appears she may have been attempting to attach a suffragist banner to the horse, Davison’s exact intentions remain unknown.

Davison and Richardson were derided in the popular press, as were many of the other suffragists. While many doctors signed petitions asking for the government to suspend the practice of force-feeding hunger strikers because it was inhumane, several others co-wrote an editorial in the British Medical Journal saying that the suffragists were only being treated the way any other lunatics refusing to be fed would have been treated. After the 1913 Epsom Derby, reporters focused more on the horse (almost miraculously unharmed) and the jockey (only minor injuries, but he would kill himself less than a year later) than on Davison. Richardson was sentenced to six months in prison, the maximum penalty for destruction of a work of art in the UK at the time. The Toilet of Venus was not, however, destroyed, and the holes were eventually repaired by art restorers. (The Toilet of Venus would be attacked again, this time by climate protestors, in November 2023).

Climate activists engaging in disruptive protests at museums have cited Mary Richardson’s attack on the Rokeby Venus as precedent. Mary Richardson, for her part, would probably not find political alignment with climate protestors. After the height of suffragist protesting, Mary Richardson went on to take a leadership position in the British Union of Fascists. Richardson left the British Union of Fascists in the mid 1930s, in part because she had become disillusioned with the Fascist commitment to women’s equality.

Part 4: Summation

When I started writing about the Rokeby Venus, I thought I would (1) come to some overarching conclusion that tied together my thoughts on protest, art, and performance and (2) find a lot of fun opportunities for good butt jokes. I was wrong on both accounts. When I was reading about these three works and the various forms of protest and vandalism connected to them, almost every article or essay or think-piece ends by deciding which forms of protest are acceptable and/or successful. I’m not sure that’s even answerable. (Acceptable to whom? Acceptable contemporaneously or acceptable in retrospect? Acceptable why?). I’m not even sure how one could come up with metrics to define success. Do the protestors themselves believe the action was successful? Is it successful if it changes someone’s mind? Is it successful if it doesn’t change anyone’s mind but it still gets their attention?

I find it more interesting to just consider how the protests differ. The Rokeby Venus attack is the only one of the three that damaged the work of art itself, although it was repaired to a state that a casual onlooker would never have known that had it been damaged. The specific performance of An Enemy of the People, was certainly irrevocably changed, but there’s no indication that the protest affected other performances of that (or any future) revival, and further who is to say whether or not the interruption “destroyed” or even “harmed” the performance. Certainly some patrons were unhappy with or unimpressed by the demonstration, but most of the media coverage suggests at minimum a fascination with the event and how it echos themes from the play itself.

The Little Dancer, Age 14 attack in some ways seems like an outlier, in that the work of art itself seems to have little connection with the message of the protest. Even beyond the parallels of Emmeline Pankhurst as a modern-day Venus, Richardson’s choice of the Rokeby Venus carries a sociopolitical significance. Richardson would even say that she was partially inspired to choose the Rokeby Venus because she did not like how “men visitors gaped at it all day long.” Yet, it also seems to be the protest of the three that has garnered the most specifically political opposition. The choice to prosecute the offenders with conspiracy charges seems just as much as an outlier as the initial protest itself.

In the end, what I find most fascinating is not that that these three art works are now linked, nor that these three protests are all linked, but that there are now six things that are tied together: three acts of creation and three acts of activism. Degas once wrote that “A painting is a thing which requires as much trickery, malice, and vice as the perpetration of a crime,” but only the latter three acts are likely to be viewed as crimes today (the Velázquez may in fact have skirted “criminality” charges with the Spanish inquisition, the Degas is maybe a crime of aesthetics to some, but Jeremy Strong remains innocent). Yet, in looking at how these activist actions play and repeat and change overtime, we see the connections between protest and art more clearly. Maybe protest, like acting or sculpting or painting, exists in a plane where there is more insightful criticism to find than “is it acceptable?” or “is it successful?”. Maybe protest, like acting or sculpting or painting, is an act of vulnerability, conviction, and the hope that someone, somewhere, will pay attention.

Some Sources and Further Reading:

www.visitnorway.com

Feldman, Adam (2024). Activists disrupted An Enemy of the People on Broadway last night, and mayhem ensued. TimeOut New York. Online.

https://www.npr.org/2024/04/26/1247317476/climate-activist-degas-dancer-national-gallery-sentenced

https://www.nga.gov/features/modeling-movement/little-dancer-original-state.html

Wilson, Bee (2015). “Throw it Out the Window.” The London Review of Books.